The family

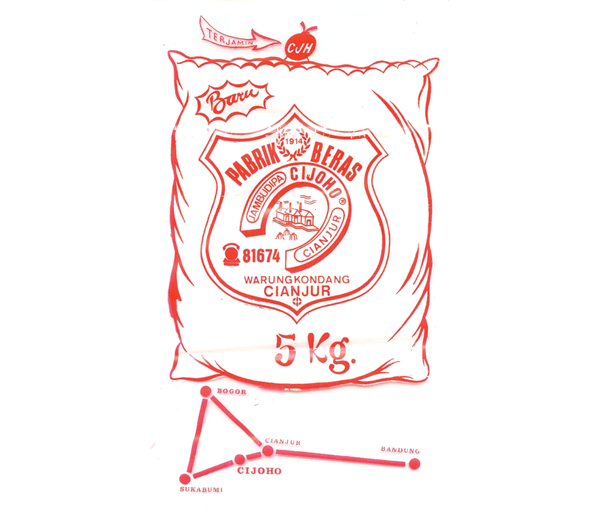

Tan Sin Hok is born on March 28th 1902 in Tjipadang, West Java, as the youngest son of Tan Kiat Tjay (1870-1910), who runs a rice-husking plant, and his wife Thio Hian Nio (1875-1948). His two elder brothers are Sin Ho (1898-1964) and Sin Houw (1900-1994). Hok’s father is a ‘well-off’ Chinese, with three sons and a flourishing Pabrik Beras in Tjipadang in the Tjiandoer area of West Java. In 1910, when Hok is eight years old, his father dies of an infection of his leg. The three boys close the coffin, which is standard furniture in the living room, by driving long nails into the lid one at a time. Tan Kiat Tjay’s grave is at the Chinese cemetery of Pasir Ayam near Tjidjoho in the Tjiandoer region.[1]

Now a widow, Thio Hian Nio, together with her three children, is appointed to her late husband’s elder brother, Tan Kiat Hong (1868-1924), who also runs a blooming rice-husking plant, and his wife Phoa Hian Nio (1861-1943). His younger brother Tan Kiat Goan (1876-1927), a Lieutenant of the Chinese in Tjilaku[2] , becomes their testamentary guardian.

Bag of rice, 5 kg, Cijoho near Tjandjoer (1982)

The boys grow up in Tjidjoho. They call their aunt Tan Kiat Hong “mother”, whereas their own biological mother is now named “baboe”, i.e. nanny, as Hok recounts in his letter from June 11th 1929. His mother works in the kitchen and is not supposed to address her brother-in-law directly. All communication occurs via her son Sin Houw. Finally, after 15 years, the eldest son Sin Ho marries, through which she now becomes a ‘mother-in-law’ and is rehabilitated as a consequence. As is customary in Chinese families, mother-in-law “Mamma” gets to live in with each one of her sons in rotation.

Education

At home, Hok speaks both Malay and Sundanese, like his mother. In 1907, at five years of age, Hok attends the European Primary School (ELS) in Tjiandoer together with his brothers. Next, all three attend Koning Willem III grammar school in Batavia, where they graduate under Hok’s supervision in 1919. To their fellow students, Hok, Houw and Ho are respectively known as “Ferdinand”, “Eduard” and “Bertus”.

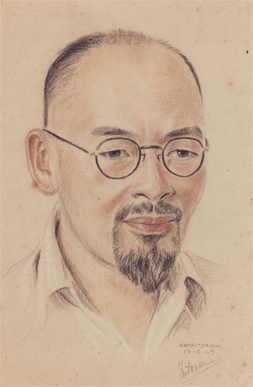

By the end of 1919, Sin Hok and Sin Houw leave for Holland to study, while Sin Ho stays in Tjipadang to look after the family business. Hok studies mining engineering in Delft and Houw, who initially plans to study agricultural science in Wageningen, once in Holland, decides to stay closer to his brother and enrols for chemistry in Delft. The two brothers share one morning dress and one dinner jacket – too small for Houw and too large for Hok – which they wear in turn to go to examinations and parties. After his promotion in Delft in 1927, Hok goes on to do the research on foraminifera in Bonn that will earn him a worldwide reputation.

Marriage

When Hok is still quite young, the family arranges a marriage for him with his cousin Thung Sin Nio (Betsy, 1902-1996). However, after 10 years of studies in Europe, he returns on June 8th 1929 with his wife Eida Schepers. Three days after the return, Hok writes about the reunion with his native country and his family. He describes how both he and Eida pay honour his Chinese ancestors by burning incense at the family altar in Tjidjoho. (cf. letter 1929-06-11).

Hok’s brother Houw marries the woman whom the family have selected for him, Bong Fa Ni (or Fanny, 1909-1998), in 1932. He goes to inspect her at the Nederlandse Ursulinenklooster on the isle of Banka[3] , where she attends a boarding school. Her mother has had her adopted by a childless relative at an early age (see: 1932-11-08). Houw and Fanny are to have no children of their own.

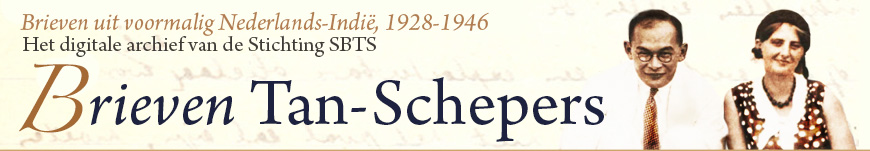

HOK

November 8th ‘32

Greetings. Houw is getting engaged soon! Good for him. He’ll be surprised how much I already know about her family. She is a Bong, but her original name is Lang, after her father. She was adopted by a maternal uncle. Her grandfather or great-grandfather was a Dutch mining engineer who left his wife and children when he retired. He wouldn’t be the first! She’s supposed to have a European appearance and was raised by Ursuline nuns. A rather complicated combination, almost as complicated as our children.

HOK

15-11-‘32

Greetings. The day before yesterday I attended Houw’s engagement ceremony. The only ones present were relatives from both sides. The highlight was the exchange of the rings. Houw was extremely happy and Fanny, or Fa Ni (Beautiful Flower) in Chinese, was as well. The girl is truly sweet, with a gentle nature and, what is unusual for Chinese girls, she is completely free in her doings. I may call her by her name, for instance, which isn’t customary to Chinese. She immediately came and sat next to me to chat about Eida. Houw couldn’t be more in luck, I must say, both with the girl and his new in-laws. Really, I have never spoken to such a liberal father as this master of the house - Fanny’s real father, I mean. He is completely averse to conventions – which most Chinese are not – and values essence over form. So, I had a nice time, in all. I talked to Fanny for quite a while and I’m happy with my new sister.

I’m sure she’ll get along with Eida very well. Therefore she’ll come and visit us soon. She has a great sense of humour too. The mother-in-law-to-be invited us as well. Fanny herself speaks proper Dutch.

Inheritance

To compensate for the debt of honour of ƒ18.000,- that Tan Kiat Hong has paid from his own resources to fund Hok’s and Houw’s studies in Holland, Sin Houw takes a job as an administrator at the tea factory of “the” Aunt, Kiat Hong’s widow. Tan Kiat Goan, who acts as the testamentary guardian of the three young men, has always made it seem as if he paid for the studies in Holland out of his own pocket. When Hok and Houw return to the Indies, it turns out that they have paid for their education from their own inheritance. Hok’s letters clearly reveal a row about money. The guardian’s widow is called the “Mean Aunt” (1929-06-11. See also: 1929-06-24(2) and 1929-07-02).

The Tjipadang rice factory run by Sin Ho falls into liquidation in the early 1930s, after which Sin Ho, together with his wife and four children, continues to live off Houw and Hok (1932-06-08, 1936-01-16, 1936-03-10, 1937-02-15 and 1937-03-02). In 1973 Eida signs a document confirming that she will make no further claim to the piece of land that Hok is in fact still entitled to.

Grandparents

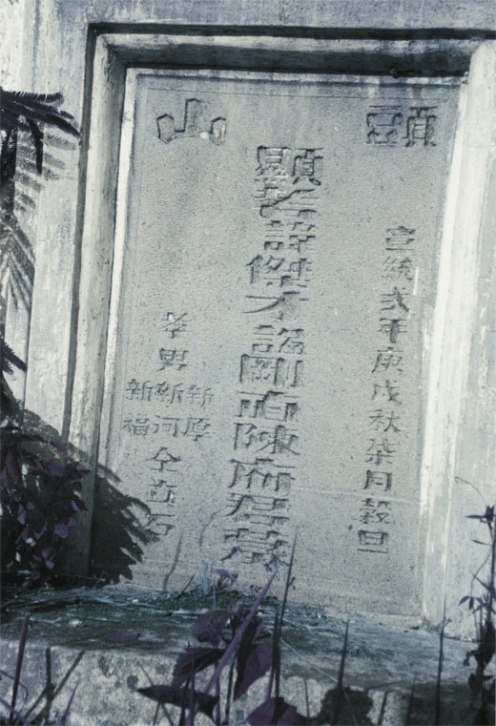

Around 1850, Hok’s grandfather Tan Se Kho (†1891) travels from the Chinese coast province of Hokkiàn (Fukien/Fujian) to Java on a small boat carrying commodities.[4] On West Java he marries Tjay Tjoen Nio (†1914), a Sundanese Chinese. On the premises of the rice factory in Tjidjoho there are two graves. To the left of the entrance, behind a high gate, we find the sumptuous grave of Tan Kiat Hong with his image on it. Opposite, hidden among the sawahs, there is a grave with elaborate reliefs of boats and waters, which turns out to be Tjay Tjoen Nio’s, not Tan Se Kho’s. She and Tan Se Kho had three daughters and three sons [See: family tree], but on the tombstone the names of the three daughters and only two sons are engraved. Hok’s father, Tan Kiat Tjay, is left out. The reason for this might be that he entered into a marriage with a Sundanese of too little Chinese blood. This may also account for the fact that Tjoen Nio came to be called “Baboe” by her sons and was supposed to work in the kitchen when she became a widow.[5]

Children

Already in 1930, long before the birth of his first child, Hok is called to account by his cousin Betsy Thung regarding the upbringing of his children. She accuses him of disloyalty to his Chinese ancestors (cf. 1930-02-11):

Betsy has asked me if I will raise my children the Chinese way. I replied that their upbringing will be in keeping with my principles. These may be different ten years from now, but I will live a life rooted in conviction. It is impossible to live by an educational approach that is at odds with conviction. Moreover, it is not the father who raises the children, but their mother first and foremost. The father often has a supporting role at most. Betsy has never considered this. I believe she thinks of me as a heretic. So be it.

Eida and Hok give their children European first names as well as additional Chinese names. According to family tradition, the two sons have both a first name and a generation name after the family name. Axel (1932) is called Tan Siang Tjoen (“Spring Bringing Happiness”) and Gijsbert (1942) is called Tan Bing Tjoen (“Clear Spring”). Both names are spelled according to Hokkiàn Chinese. Lisa’s name, Tan Hsi Ch’un (“Sunny Spring”), is spelled in Mandarin Chinese. One major deviation from the family traditions is her third name, the generation name “Spring”, which is the same as her brothers’, instead of the traditional “Nio”, meaning “Girl”. Hok comments in his letter from October 1st 1935:

In case it’s a girl, the Chinese name we’ll give her is ‘sunny spring’. Thus, she’ll have a generation name as well. To conservative standards a girl shouldn’t bear a generation name, but in the event we shall deviate from that, like more modern Chinese are now doing, if only to show that we don’t intend to consider a girl in any way inferior to boys.

Childless

Eida, just over four months a widow, leaves for Holland on April 16th 1946. Sin Houw, Fanny and Hok’s ‘true’ mother have come to Batavia to see her off. There, Fanny asks Eida to consider leaving her youngest son to live with her and Houw at Java, so that they may have a child of their own and Gijsbert may have a father. But Eida cannot find it in her heart to do so.

Hok, Tjimahi, June 19th 1945

When Mamma asks where Hok has gone, the family reply in Sundanese: “Hok has left on a long journey”. After all, Hok did a lot of travelling in his days. The explanation for this painful lie comes out in 1992: “It was for love, both for Mamma and the family. You never know what troubles such grief may cause a mother.”

---

* The maternal family tree is unknown. Sources: 1.) The Tan-Schepers archive; 2.) oral history via Tan Sin Houw (1900-1994), Hok’s favourite brother; 3.) the family tree of Tan Se Kho and Tjai Tjoen Nio by Axel Tan, 2010).

[1] The grave can be identified by the names of his three sons. In 1982 it turned out that the man who got paid to maintain the grave had accidentally taken care of someone else’s grave all those years. “Never mind”, said Houw, “it’s the intention that counts”.

[2] Like the Captains, Majors etc. of the Chinese, the Lieutenant belonged to a group of Chinese civil servants appointed by the Dutch V.O.C. They were part of the colonial administration and kept the register of marriages, births, etc. Also, they were important intermediaries between the colonial authorities and the Chinese community. The Chinese lived together in so-called ‘Chinese camps’ and in order to leave the camp one had to ask the Lieutenant for permission.

[3] Banka: Indonesian island between South Sumatra and Borneo.

[4] During the Opium Wars, Xiamen, the capitol of Fujian, was taken by the British. Many young men left their homeland in search for a better future. Their descendants are the so-called Peranakan Chinese, who are of native birth and no longer speak the Chinese language.

[5] Tan Kiat Tjay marries Tjay Tjoen Nio around 1897. In those day many European, Chinese and Arab men lived with a njai, i.e. a housewife and concubine.