Communication

The letters of Eida and Hok display a strong urge to communicate, regardless of the actual content or the subject matter at hand. Whether it is the present economic situation, fashion, a meal, a ride or a party – each subject is conveyed with intensity. There are various reasons why this is so, such as the obvious loving proximity to the addressees, i.e. Eida’s parents, the communicative skills with which both Eida and Hok are endowed as exponents of a writing culture, as well as their general knowledge, curiosity and joy of writing.

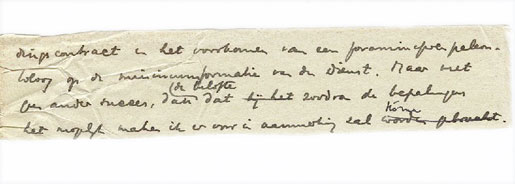

What is decisive for the sense of urge is, however, the format of the correspondence itself. The confines of just a few sheets of paper, which were completely covered with writing on both sides, including the margins, the low-frequency schedule of the mail transports that, in addition, took a while to get a letter from Java to Holland, and the relative novelty of modern means of communication, such as the telephone, deeply determine the ‘pressure’ of what is being written. Quite literally, at times:

It is annoying but if they don’t deliver what you’re waiting for, please remember that the next flight will surely bring the letter. Every now and then we are suddenly being disturbed and cannot finish the letter in time. But then again, there are 3 flights a week. Don’t jump to conclusions as if we’re not posting them soon enough or something is wrong. For if there was, we would surely write! (Eida, August 5th 1938)

On March 1st 1933 Eida announces that as of that day, all letters will be written on airmail stationery. The decision not only concerns the speed of mail traffic:

So from now on you won’t be receiving any mail letters anymore. (…) I have a sense that you can write much more on this paper compared to the regular stationery, because it allows nice and small writing.

Even so, she takes some extra precautions (idem):

I’d better skip the paragraphs and write in one stretch, otherwise it would be a waste of paper.

The correspondence itself is a regular topic of discussion. What was it like in practice?

Mail boat

The Tan-Schepers collection opens with a postcard dated April 17th 1929, when the newly-weds are on their way to Java, a few days after their marriage. The journey includes Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and Genua, where Eida and Hok embark on the diesel ship Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft around May 20th 1929.

In the first letter from Java, dated June 11th 1929, Hok describes the reunion with his native country and his family after ten years in Europe. On June 24th 1929 an additional telegram confirms the safe arrival, but from then on a weekly letter to Eida’s parents in the Hague is on its way.

“‘Mailing’ - a new verb to our vocabulary!” Hok writes in that first letter. ‘Mailing’ entails: posting a letter every Tuesday for the mail boat, which not only transports mail to Holland, but cargo and passengers as well. In time, specialized freighters and passenger ships will come into use, like the diesel ship Christiaan Huygens that brings Eida, Hok and their two children back to Java after their leave in April 1938. The interval between sending a letter and receiving an answer took seven to eight weeks. On November 17th 1929 Eida writes:

Just read though your letter twice. How chatty indeed your writing is today! (It is the one from Oct. 21 and 22).

Airmail

As of October 1930, Eida and Hok occasionally send airmail paper to Holland to get an answer sooner. On February 23rd 1933, Eida writes:

How about writing only via airmail from now on? It will cost both us and you an extra ƒ1,20 a month at the most and it makes such a difference in the messages (…) – these sheets are perfect for writing on both sides and they have a lot of space as well. We’ll send our snaps and so on via boat mail and in case we have a lot on our chest, we can always send it by sea, but this seems so nice, in a way, also in answering – things do take ages now – (…) Whenever we receive airmail, we realize how much time we lose simply because of sea travel, while now it shouldn’t take more than 10 days. It does seem like the right thing to do.

One month later, on March 9th 1933, she writes:

We are wondering when you will switch over to regular airmail as well – I’m really running out of patience to wait for these old messages, I cannot digest them, need fresh ones!

Meanwhile, Eida and Hok have switched to 5 grs. airmail paper with extra prepay for enclosed photographs. In general, Eida’s and Hok’s use of the amount of pages amounts to a ratio of 3 : 1. Sometimes, Eida leaves only margins or even an odd scrap of paper for Hok.

Telegrams

On special occasions, such as the births of the children, a telegram is sent.

Visit to the Netherlands Indies

In July and August 1931, Eida’s parents come and visit the Indies together with their daughter Emma, Eida’s younger sister. The last letter before the visit is dated July 24th 1931 and first one after it is from October 2nd 1931. Some photographs of the visit survive.

KLM vs. the Postjager

By the end of 1933, KLM meets the competition of the “Postjager” express mail airplane. The plane was constructed by aircraft builder Pander as commissioned by the shipping industry, where there was growing concern about KLM’s monopoly position. The Postjager takes off on December 9th 1933 on its way to the Netherlands Indies and is scheduled to deliver return post in Holland before December 31st. However, because of engine trouble, it strands in Italy and, instead, KLM’s express plane the ”Pelikaan” delivers all return mail before the turn of the year. In January 1934, the Postjager returns to Holland – too late in the day. On January 8th 1934, Hok writes:

The Postjager has earned the following nicknames: Pest-jager, Last Post-jager and Post-wagon.

The KLM remains firmly in the saddle, but the punctuality of the correspondence has been temporarily disturbed for Eida and Hok.

The letter of December 26th 1933 is sent by regular airmail, because it just misses the last collection for the Pelikaan (KLM). The one dated January 4th 1934 is sent by express mail with the Pelikaan, and another one, dated […], is sent both by Postjager express mail and by regular mail, as Eida and Hok observe in their letter of January 23rd 1934. Sometimes they bring a letter to Andir airport themselves in order to catch the last collection. In the photograph below, the boy standing under the wing and pointing to the plane is Axel.

Regularity and frequency

For any traveller to the tropics, regularity and a certain speed in contacting the motherland were vital. Hence the repeated interest in air traffic, be it mail or regular, safe or crashed:

The Emeraude has crashed with Pasquier. It goes to show what a feat the Pelikaan pulled off. With its fine organization, KLM beats every European airline. (1934-01-04)

Similarly, the adventures of the Uiver are discussed at great length: a child being baptized “Uivertje” (1934-10-30), the heroic reception of the Uiver crew, including captain Koene Parmentier (1934-11-06); the crash of the Uiver (1934-12-25) and the fatal accident of the Pelikaan’s Christmas flight co-pilot with the Leeuwerik (1935-07-22).

On leave

Hok is entitled to paid leave to Holland once he is given the same rights as his Dutch colleagues (1936-01-13 and 1936-08-24). In June 1937, Eida and Hok embark on the diesel passenger ship Dempo (Cf: 1937-06-18). They have hired a sea-baboe to look after the children (May 18th 1937). The letters about the family visit to Holland that were written to Eida’s parents are included in the archive. Of the joint holiday with Eida’s parents to Adelboden, Tirol, in February 1938 only photographs exist. The return trip is on the passenger liner Christiaan Huygens. The next letter from the Indies is from April 8th 1938.

Stagnation

Because of acts of war by Germany, who have invaded Poland in September, mail traffic to Europe is temporarily cut off between August and October 1939. On October 1st 1939, Hok writes:

I hope you have received our news from around September 1st. Things were very confused because of the outbreak of the war. That is probably why the mail wasn’t delivered. Maybe the letters were detained somewhere.

One month later we read:

What a nuisance that our letters have been opened by the censor, but it seems that many messages with our postal codes end up in Germany and are harmful to the allied. So many Germans and Dutch who live here consider Germany as their spiritual homeland.[1] (November 21st 1939)

Miscommunication

In intercontinental mail correspondence, miscommunications are not easily resolved. We find one such instance between Eida and her mother from August to November 1939: in all, it takes four months to resolve the matter at hand.

Mail during and after the war

Eida and Hok seldom use the alternative mail route via Curaçao, where Eida’s brother-in-law is the Dutch Attorney General. Eida’s sister Anneke manages to get some letters to Holland along with his diplomatic mail. Eida’s letter from April 1941 has every name abbreviated to initials to prevent identification (cf. 1941-04-16). Eida and Hok resume the correspondence after August 1945. From December 1945 on, Eida continues to write, with the aid of Axel. A handful of letters sent from Holland to the Indies remains from this period.

Writing materials and stationery

As long as the letters go to Holland by mail boat, Eida and Hok use both ruled and unruled (writing pad) stationery. From May 1930 Hok in addition has his own custom stationery.

Once Eida decides she’s had enough of ‘old messages’ and wants ‘fresh ones’ instead in March 1933, they switch to thin sheets of airmail stationery, which, according to custom, they cover with writing completely, back and front. Hok uses a fountain pen, whereas Eida uses a dip pen or a pencil, when she writes lying on her bed. In November 1930 we read:

Meanwhile I’m terribly annoyed by an old dip pen, a wobbly lectern and an inkpot that is almost empty.

Finally, in December 1931, she has her own fountain pen:

Look at my writing! “The” fountain pen from Rotterdam has arrived. It writes really smoothly, the only drawback being that when it is dry, I have to thrust it a little to go on writing. Still, it is so much nicer than having to dip in that pen all the time. (…) I dare not bring it in my purse; Hok says it will leak at the slightest bump.

In 1932 Hok buys a typewriter with the “petrol money” he has earned as an external advisor to an oil company. On July 7th 1932, Eida writes:

Hok is so busy, both with the mapping and the Petrol, (…) besides he is supposed to type out all the letters himself, as 4 full copies are required for Holland, Madoera and himself. I suppose we should buy a typewriter so that he doesn’t have to go to G.B. all the time and I could even practice some myself.

1932 is the same year in which Eida becomes involved in the world of women’s rights movements, such as the VIVOS, IEV, IEVVO and IEVA. The typewriter is of great help to her.

Photography and film

Sending photographs is part and parcel of the communication from early on, as sending films becomes at some point. Thus, the letters contain a great many ‘captions’ to go with the photographs and the films that are being sent.

Radio contact and telephony

In 1929, no direct intercontinental telephone lines are available on Java. Early in 1930 the family members in Holland and Java once again hear each other’s voices over the Malabar radio station. On January 7th 1930, Eida and Hok comment:

A little (time) left to cheer over our talk. The way the voices came through, even better than talking over the telephone. (…) Being able to traverse 10.000 miles so easily. We were seated in comfortable chairs, relaxed, around a small round table with a swivelling microphone on it, each with a headphone over our ears. (…) Those three minutes just flew by, didn’t they? 7 Persons was a bit too much, really, less than half a minute each (…) We all had a small paper in front of us with points to address, but we didn’t manage to cover them all (…).

In 1930, a three-minute conversation over Malabar radio station would amount to ƒ33,-, roughly the equivalent of €700,- in 2013. On Malabar a monument (“A kind of globe”, according to Hok) was unveiled in honour of the station’s founder (See: January 28th 1930).

Regarding telephony, Hok writes on July 21st 1929:

The one thing that is old-fashioned in our house is the telephone we got yesterday. It’s a wall model from long ago. A big box with a crank for the bell. Although we share our number with the neighbours, we each have our own set and needn’t barge in on one another. And we both pay ƒ10,50 a month.

-----

[1] During this period, mail traffic from Batavia runs as usual, as we can understand from the letter archive of Eida's sister. Many influencial positions in Bandung are being held by Germans who sympathize with the Nazis. (Hok 1939-11-06).