The family

Eida Schepers is born on August 28th 1906 in Winschoten as the second of three daughters. Her parents are Menno Antonius Schepers (1875-1967) and his wife Sara Elisabeth Henriëtte Cohen (Sari) (1877-1965), and her two sisters are Anneke (1905-1982) and Emma (1908-2004).

Menno Schepers meets Sari when he is reading classics at Groningen University and visits the parental home of his good friend Isaac Cohen, her brother. The Schepers-Cohen family moves to The Hague when Eida’s father takes up his new job as a teacher of classics at Haganum College in The Hague, a position he will hold until his retirement in 1940. Eida’s mother has finished the Domestic Science School in Groningen. She is one of the first married women to cast off the corset and leave her ankles uncovered. Hence the chorus of the family song at Menno’s and Sari’s wedding:

The source of ailments we are told

Is the corset, so behold:

Forget the confines of the norm

Wear the dresses of reform

The last chorus ends on: “Throw the corset out”.

Because of her marriage to Menno, Jewish Sari survives the Second World War. Her sister Leidie Goudsmit Cohen is killed in Sobibor in 1943. Two of Sari’s cousins, Rebecca and Annie Biegel, commit suicide in Westerbork in the same year.

Education

Sari strongly encourages her daughters to attend grammar school in The Hague and learn a trade. Anneke eventually takes a degree in law at Leiden University, where Eida studies Dutch Language and Literature, and Emma becomes a qualified medical analyst. In the letters, Eida often mentions her student fellowship P.S. en its nine members:

December 7th is the 4th foundation day meeting of P.S. Would you please send a cake on our behalf (…) On it, I would like to have 8 peas in a pod with one rolled out toward a brownish bean and a text saying (…): “Pea and bean from far away / send this to you on this day”. (October 31st 1931)

Having met Hok in 1928, Eida quits her studies after two years and takes courses at the Colonial School in The Hague. Once in the Indies, she writes to her mother that the Colonial School doesn’t prepare women for living with a Chinese spouse, for whom food is such an important aspect of life:

With Mamma around I didn’t manage to fix us a nice little diner (…) because I’m not in her league as far as cooking is concerned. (…) So you see, my dears, there’s no need to cram away at Domestic Science Schools when you end up marrying a man who doesn’t appreciate Dutch food anyway! (April 21st 1931)

Marriage

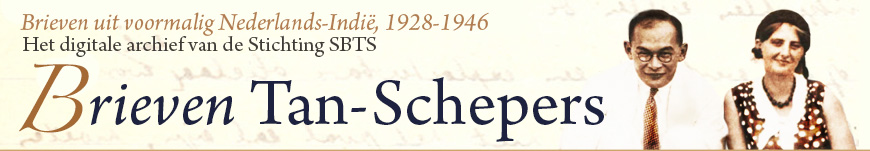

On February 18th 1928, there is a student party at Hugo Hijmans’s, the family doctor of the Schepers-Cohens. Hijmans urges Sari to send her daughters because the party is short of girls. However, Anneke and Emma have other plans and instead talk Eida into it. This is where Eida and Hok meet for the first time. Three months later, on May 26th 1928, they get engaged. The date of the party will eventually become engraved in Eida’s wedding ring along with the wedding-day.

Having an Indo Chinese as a future in-law is a first for both the Schepers and Cohen families. Mother Sari is particularly in favour of the engagement, for she is convinced that mixed marriages will eventually eradicate racial discrimination altogether. On her deathbed she recalls a major grief from her own childhood: “Sari cannot join in, for she is Jewish.”[1]

Eida’s maternal grandparents are Bennie Cohen (1833-1912), who is a lawyer in Groningen, and Anna Schaap (1845-1911). Anna’s eldest sister Aleida Schaap (1843-1894), whom Eida is named after, is the mother of the painter Isaac Israels and his sister Mathilde. Their father, i.e. Sari’s uncle, is the painter Joseph Israëls (1824-1911). In her letters from Bandung, Eida often mentions Auntie Masje (i.e. Mathilde), who provides her with literature and advice concerning the women’s rights movements she is involved in.

[1]Hok's letters from 1928 and 1929 to his future mother-in-law ("Dear Madam") clearly illustrate his awareness of racial and cultural discrimination.